Participatio Activa & Participatio Actuosa

by Andy Milam

In 1987, my mentor Monsignor Richard Schuler wrote regarding full, conscious and active participation. This was one of the very first principles that he would teach when speaking catechetically about the liturgical action and how man relates to it. This was the very first principle that he taught me. Over time, I will be expanding this principle; writing about how we can enhance our participation in the liturgical action and how this can be applied to everyday assistance at Holy Mass.

The following are the words of Monsignor Richard J. Schuler:

With the constitution on the liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, issued in 1965 by the Second Vatican Council, everyone became very conscious of personal participation in the sacred liturgy, particularly in the Mass.

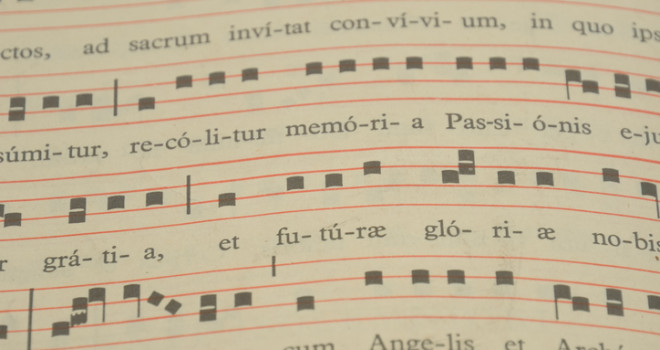

But active participation in in the liturgy was not a concept created by the Second Vatican Council. Indeed, even the very words actuosa participatio can be found in the writings of the popes for the past one hundred years. Pope Pius X called for it in his motu proprio, Tra le sollecitudini, published in 1903, when he said that “the faithful assemble to draw that spirit from its primary and indispensable source, that is, from active participation in the sacred mysteries and in the public and solemn prayer of the Church.”

[…]

The Mass of its nature requires that all those present participate in it, in the fashion proper to each.

This participation must primarily be interior (i.e., union with Christ the Priest; offering with and through Him).

- b) But the participation of those present becomes fuller (plenior) if to internal attention is joined external participation, expressed, that is to say, by external actions such as the position of the body (genuflecting, standing, sitting), ceremonial gestures, or, in particular, the responses, prayers and singing . . .

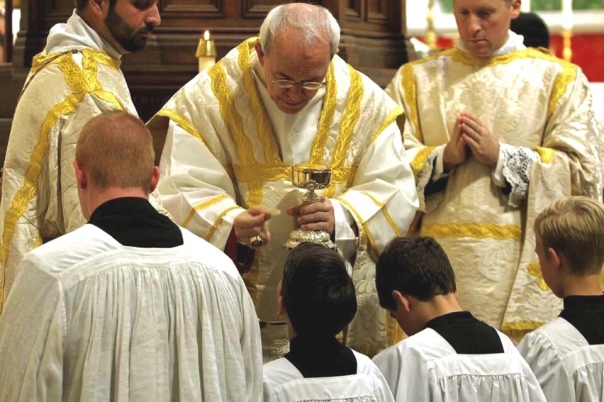

It is this harmonious form of participation that is referred to in pontifical documents when they speak of active participation (participatio actuosa), the principal example of which is found in the celebrating priest and his ministers who, with due interior devotion and exact observance of the rubrics and ceremonies, minister at the altar.

[…]

It is made clear that it is baptismal character that forms the foundation of active participation.

Vatican II introduced no radical alteration in the concept of participatio actuosa as fostered by the popes for the past decades. The general principle is contained in Article 14 of the constitution on the sacred liturgy:

Mother Church earnestly desires that all the faithful should be led to that full, conscious and active participation in the ceremonies which is demanded by the very nature of the liturgy.

Such participation by the Christian people as a “chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a redeemed people” (I Pet. 2:9; 2:4-5) is their right and duty by reason of their baptism.

In the restoration and promotion of the sacred liturgy this full and active participation by all the people is the aim to be considered before all else; for it is the primary and indispensable source from which the faithful are to derive the true spirit of Christ . . .

[…]

A true grasp of the meaning of participation in the liturgy demands a clear understanding of the nature of the Church and above all of Christ Himself. At the basis of so much of today’s problems in liturgy lies a false notion of Christology and ecclesiology. Christ, the incarnate Word of God, true God and true Man, lives on in this world now. “I will be with you all days until the end of the world.” Even though He has arisen and ascended into heaven, He lives with us. The Church is His mystical Body, indeed His mystical Person. We are the members of that Body. Its activity, the activity of the Church, is the activity of Christ, its Head. The hierarchical priesthood functions in the very person of Christ, doing His work of teaching, ruling and sanctifying. Thus the Mass and the sacraments are Christ’s actions bringing to all the members of His Body, the Church, the very life that is in its Head. Participation in that life demands that every member of the Body take part in that action, which is primarily the liturgical activity of the Church. The liturgy is the primary source of that divine life, and thus all must be joined to it in an active way. Baptism is the key that opens the door and permits one to become part of the living Body of Christ. The baptized Christian has not only a right to participation in the Church’s life but a duty as well. It is only the baptized person who can participate.

The difference between participation in the liturgy that can be called activa and participation that can be labeled actuosa rests in the characteristics of baptism. It is this very sacramental seal that grants one the right to participate. Without the baptismal mark, any action we conduct at Mass, singing, walking, kneeling or anything else can be termed “active,” but they do not constitute participatio actuosa. Only through the sacrament of baptism can any action be truly participatory. Let’s say that a pious Jew attends Mass, takes part in the singing and even walks in a procession with great piety. In the same church is also a Catholic who is blind, deaf, dumb, and isn’t able to leave his chair; he can neither sing nor hear the readings nor walk in the procession. Which one has truly and actually participated, the one who is very active, or the one who has confined himself solely to his thoughts of adoration? Obviously, it is the baptized Catholic who has exercised participatio actuosa despite his lack of external, physical movement. The Jew even with his many actions has not been capable of it, since he lacks the baptismal characteristic which is the topic of discussion.

Through the necessity of baptism, it still is imperative for the Catholic Christian to take part in the liturgy actively by a variety of interior and exterior actions. This means that the internal actuosa participatio, which the indelible mark of baptism empowers, must be aided by those external actions of which he is capable. He should do those things that the Church sets out for him according to his role in the liturgy and the various conditions that age, social position and cultural background dictate. He must join participatio activa to his participatio actuosa which he exercises as a baptized Catholic. In other words, his outward actions should first and foremost be illumined by his internal action.

What are those actions that make for true active and actual participation in the liturgy? They must be both internal and external in quality and quantity, since man is a rational creature with body and soul. The Church proposes many bodily positions: kneeling, standing, walking, sitting, etc. She likewise proposes many human actions: singing, speaking, listening and above all else, the reception of the Holy Eucharist, when properly disposed. They demand internal attention as well as external execution. The first thought should not be as a formal or extraordinary minister, but rather as one who joins in worship to God, the Father. It is our first right, above all other to assist at Holy Mass and give all glory and honor to God.

The most demanding of human actions is that of listening. It requires strict attention and summons up in a person his total constructive effort. It is possible to sing, especially a very familiar tune, and not be conscious of actually singing. However, one cannot truly listen without attention to that which he is hearing. Especially in our day of media attention, whether it be radio, television or social media, we are able to tune out almost every sound we wish. To listen attentively demands full, conscious and active human concentration. Listening can be the most active form of participation, demanding full effort and attention.

The Church does not have the entire congregation proclaim the gospel text, but rather the deacon or the priest does it. It is the duty of all to listen. The canon of the Mass is not to be recited by everyone, but all are to hear it. Listening is the most important form of active participation. This is why it is often referred to as “hearing Mass.”

There is a variety of roles to be observed in the public celebration of the liturgy. There is the role of the bishop, priest, deacon (and sub-deacon), acolyte, lay reader, cantor, choir/schola, and congregation, among others; because each office has its own purpose and its own manner of acting we have the basic reason for a distinction of roles. If the lay reader or the cantor is to read and/or sing, certainly the role of the others is to listen. If the choir is to sing, someone must listen and in so-doing participate actively in the liturgy, even if during the period of listening he is relatively inactive in a physical way.

During each period of history, since Christ founded His Church, mankind has participated in the liturgy through baptism, all as members of the Church and part of the mystical body of Christ. Every Catholic Christian has shared in the right and duty of actuosa participatio. If, as Pius X insists, the liturgy is the primary source of the Christian life, then everyone must take part in it to attain salvation. Active participation is not an innovation of our day; the Church in her wisdom has consistently shared the life of Christ with her members in the Mass and the sacraments, the very actions of Christ Himself working through His Church and His priesthood. It cannot be said that because the medieval period developed a chant that was largely the possession of monastic choirs, the congregations who listened were not actively participating. Perhaps not according to post-Vatican II standards, but one must carefully avoid the error of judging the past by the present and applying to former times criteria that seem valuable in our own times. The truths of the Church are timeless. Just as Palestrina’s polyphonic Masses require the singing of trained choirs, can one assume that non-choir members in the renaissance period were deprived of an active participation in the liturgy? No, of course not. The sixteenth-century baptized Catholic did participate through listening along with other activites, as no doubt an eighteenth-century Catholic did when he heard a Mozart Mass performed by a choir and orchestra. The twenty-first century Catholic participates in the same way. Benedict XVI, Pope Emeritus said:

We are realizing more and more clearly that silence is part of the liturgy. We respond, by singing and praying, to the God who addresses us, but the greater mystery, surpassing all words, summons us to silence. It must, of course, be a silence with content, not just the absence of speech and action. We should expect the liturgy to give us a positive stillness that will restore us. […] One of man’s deepest needs is making its presence felt, a need that is manifestly not being met in our present form of the liturgy. For silence to be fruitful, as we have already said, it must not be just a pause in the action of the liturgy. No, it must be an integral part of the liturgical event. [The Spirit of the Liturgy, (SF, CA: Ignatius, 2000), p. 209]

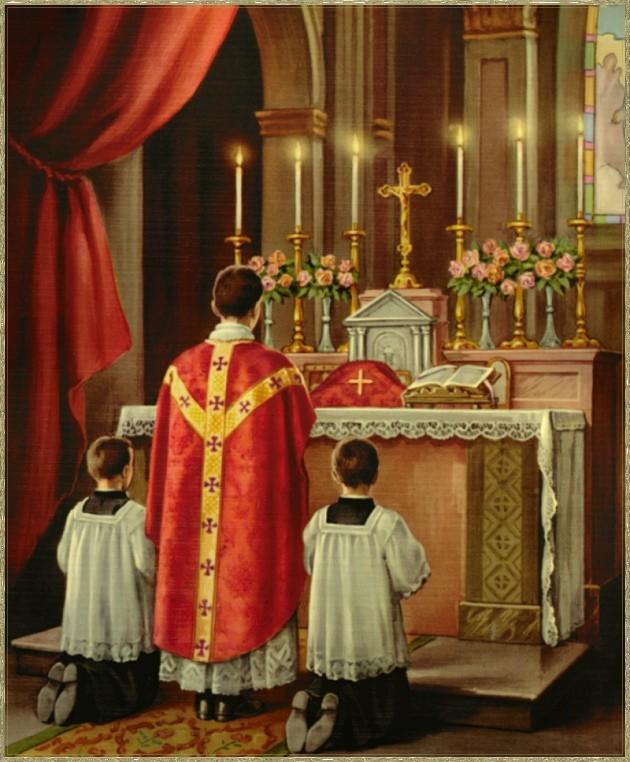

A very important aspect of the liturgy is the elevation of the spirit of the faithful who worships. At the end of the day, liturgy is the public prayer of the Church, the most visible act of adoration, thanksgiving, petition, and reparation. It is offered to God the Father, through God the Son (as an unbloody memorial of that self same bloody sacrifice on Calvary once and for all), by the power of the Holy Spirit; and as such, produces true actuosa participatio. Thus beauty, whether it appeals to the sight, the ear, the imagination or any of the senses, is an important element in achieving participation. The grand and beautiful splendor of a great church or the sound of awe inspiring music, or the solemnity of the ceremonial movement by ministers clothed in precious vestments, or the beauty of the proclaimed Word and words of the Mass, all can effect a true and salutary participation in one who himself has not sung a note or taken a step. But he is not a mere spectator as some would say, in the post-Vatican Council II era; he is actively participating because of his baptismal character and the grace stirred up in him by what he is seeing and hearing, thinking and praying.

We can conclude with this definition of participatio actuosa:

(It is) that form of devout involvement in the liturgical action which, in the present conditions of the Church, best promotes the exercise of the common priesthood of the baptized: that is, their power to offer the sacrifice of the Mass with Christ and to receive the sacraments. It is clear that, concretely, this requires that the faithful understand the liturgical ceremonial; that they take part in it by bodily movements, standing, kneeling or sitting as the occasion may demand; that they join vocally in the parts which are intended for them. It also requires that they listen to, and understand, the Liturgy of the Word. It requires, too, that there be moments of silence when the import of the whole ceremonial may be absorbed and deeply personalized. (Colman E. O’Neill, “The Theological Meaning of Actuosa Participatio in the Liturgy,” in Sacred Music and Liturgy Reform after Vatican II. Consociatio Internationalis Musicae Sacrae, Rome, 1969. p. 105.)