The Three Principal Forms of the Traditional Latin Mass

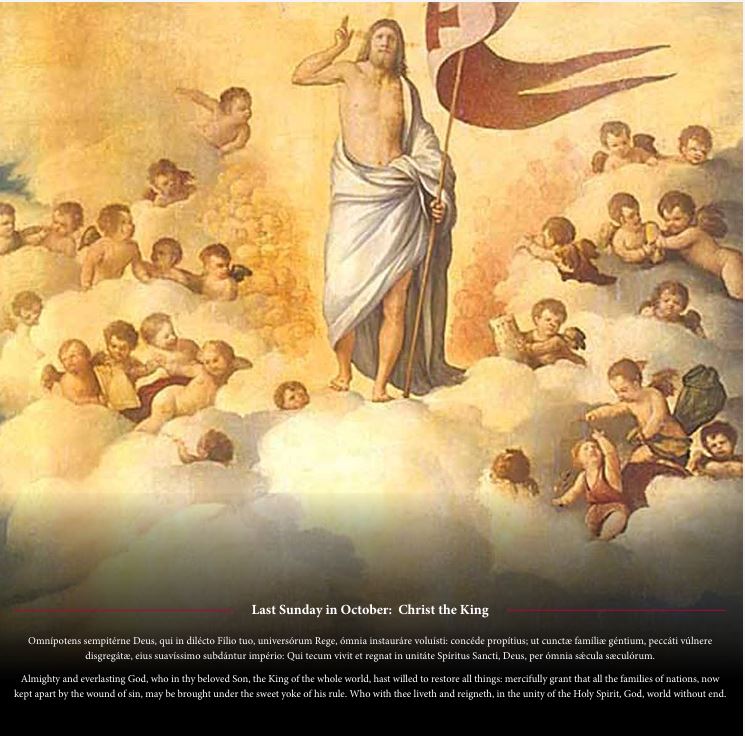

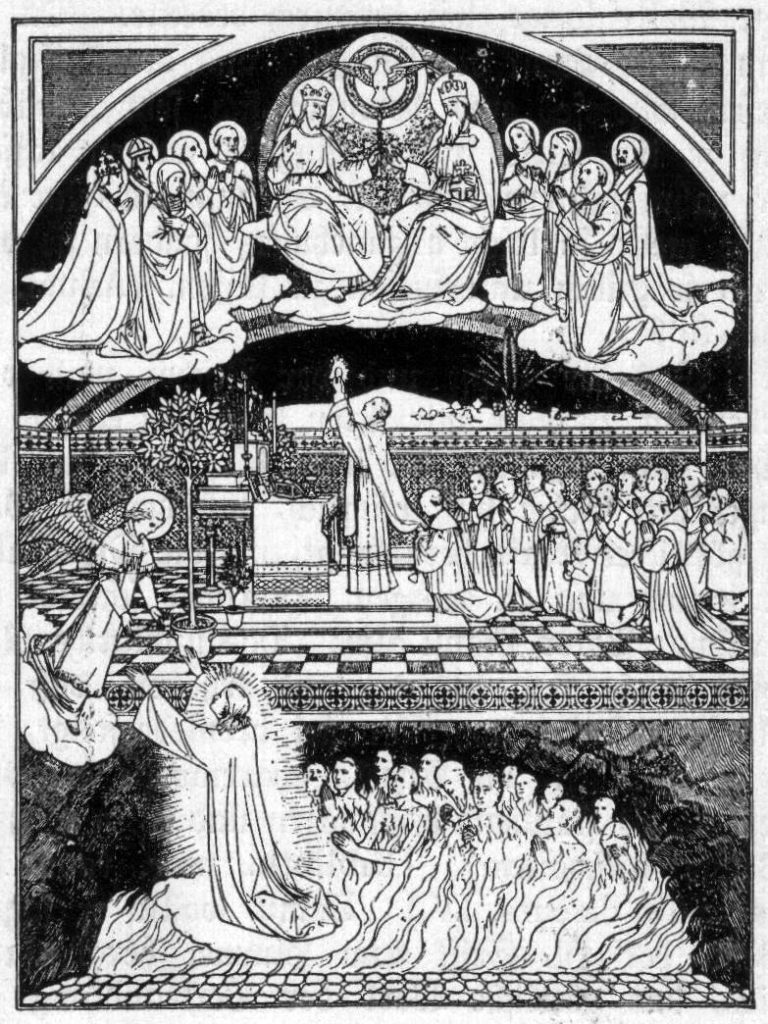

From the earliest centuries of the Church, the bishop was the ordinary celebrant of the Holy Eucharist. Surrounded by his clergy, he offered the Holy Sacrifice as the visible head of the local Church. This episcopal liturgy – later known as the Pontifical Mass – is historically the Mass par excellence. As the Church expanded and priests were increasingly delegated to celebrate Mass throughout growing dioceses, forms of the Roman Rite developed that reflected differing degrees of solemnity and available ministers. From this organic development arise three principal forms of the Traditional Latin Mass.

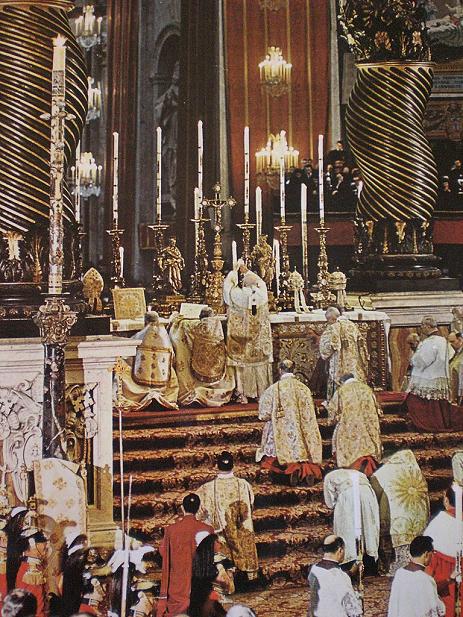

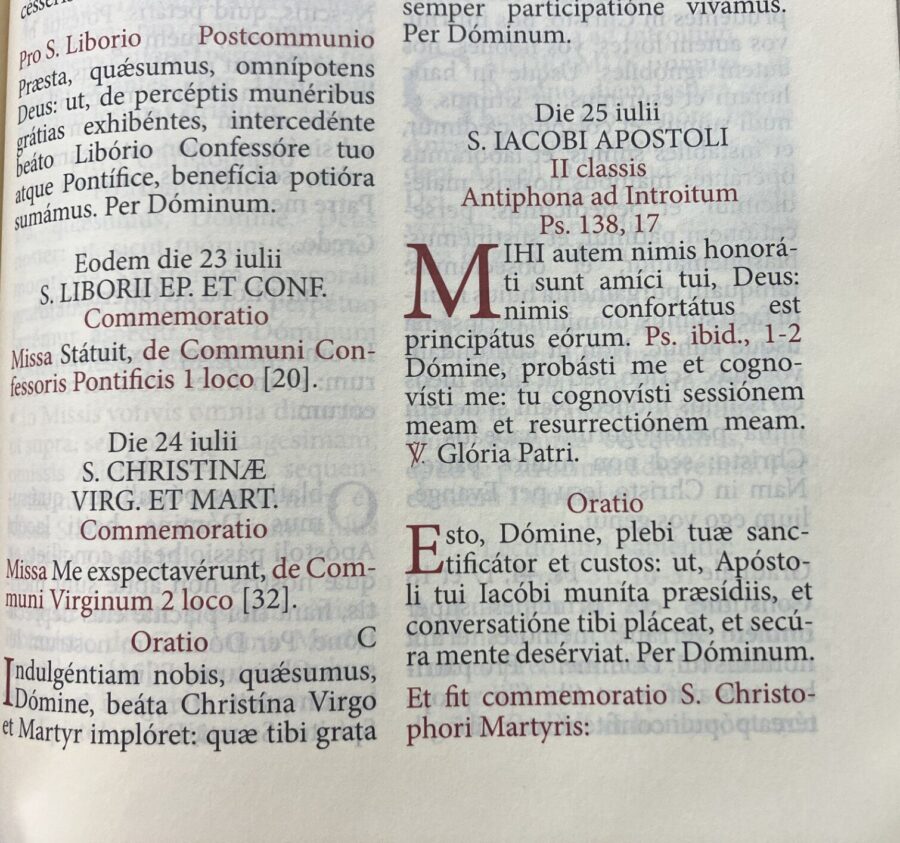

- Pontifical Mass (Missa Pontificalis), and the Solemn Mass (Missa Solemnis)

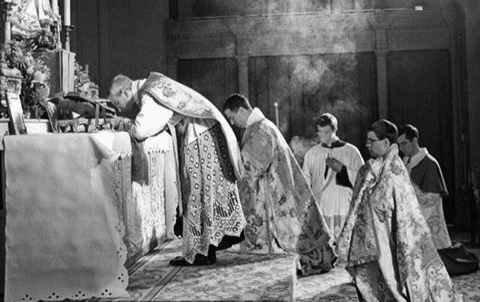

The Pontifical Mass, celebrated by a bishop, represents the highest and most complete expression of the Roman Rite. (In our modern day and age, this form is rarely seen.) It includes additional rites, vestments, and ceremonial actions – such as the use of the throne, mitre, and crozier – that manifest the fullness of episcopal authority and the hierarchical nature of the Church. When a bishop is not present, this solemnity is delegated to the priest through the Solemn Mass, celebrated with a deacon and subdeacon. Traditional liturgical sources and FSSP instruction consistently emphasize that the Solemn Mass is not a separate category, but rather the priestly participation in the Church’s episcopal liturgy.

- Low Mass (Missa Privata)

The Low Mass is the simplest and most commonly celebrated form of the Roman Rite. Offered by a priest with minimal ceremonial and without chant, it is marked by the quiet recitation of prayers, assisted by a server. This form became common as daily Masses multiplied and clergy were required to serve numerous parishes and chapels. Its restrained exterior directs attention to interior participation, emphasizing personal devotion, recollection, and the sacrificial character of the Mass. While limited experiments such as the Dialogue Mass appeared in the mid-20th century, traditional commentators and priests of the FSSP have consistently underscored the contemplative ethos proper to the Low Mass.

- Sung Mass (Missa Cantata)

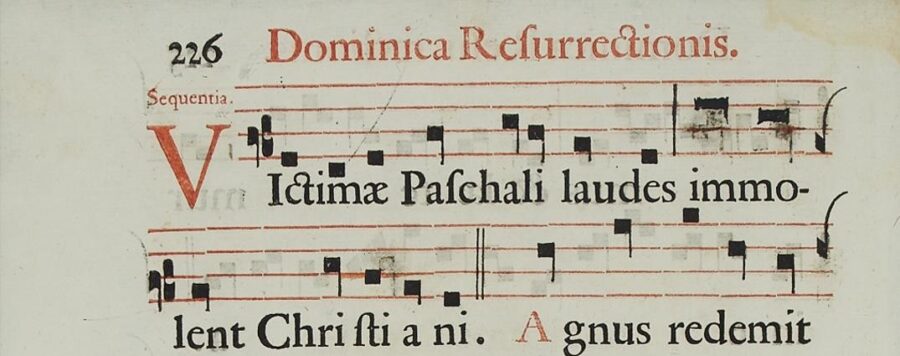

The Sung Mass occupies an intermediate place between the Low Mass and the Solemn Mass. Structurally a Low Mass, it incorporates Gregorian chant for the Ordinary and Propers and may include incense, while lacking the deacon and subdeacon required for full solemnity. The Missa Cantata developed organically in parish life where sacred music was desired but sufficient ministers were unavailable. As explained in traditional rubrical manuals and FSSP catechesis, it is best understood not as a true “High Mass,” but as a Low Mass elevated by chant and ceremonial expression.

In every form—whether episcopal, solemn, sung, or quiet—the same Sacrifice of Calvary is made present upon the altar, differing only in outward solemnity, never in substance.