First, what is a collect?

The collect is an ecclesiastical and liturgical prayer early on in the Mass, preceded by “Oremus” (“let us pray”). It’s the most important liturgical prayer of the day, as it’s also recited during the Divine Office at Lauds, Terce, Sext, None, and Vespers.

Now, if we look at the collect itself, what are the four parts:

- First, an address to God the Father (at least, most of them).

- Second, a dependent clause: we explain why we are praying to him

- Third, a petition: we’re asking for something.

- Fourth, the final clause: Per Dominum nostrum Iesum Christum Filium Tuum…

Here’s an excerpt from Fr. Adrian Fortescue in his 1912 work The Mass: A Study of the Roman Liturgy:

In any case, the logical order and style of the old collects is quite marked. Nothing in the

Missal is so redolent of the character of our rite, nothing so Roman as the old collects – and nothing, alas, so little Roman as the new ones. The old collect is always very short. It asks for one thing only, and that in the tersest language. Generally, the petition is of quite a general kind: that we may obtain what we ask, that the Church be protected in peace, and so on. It begins generally with a vocative, “Deus,” “Omnipotens sempiterne Deus,” “Domine Deus noster,” always addressed to God the Father. Then we often have a dependent clause explaining why we pray: “qui” or “quia”; sometimes merely an apposition: “auctor ipse pietatis”. Then comes the petition, often doubled in antithesis: …or a double clause not antithetic… It is in the petition-clause especially that we find all manner of really beautiful phrases, compact, saying much in few words with beautifully condensed construction, such as is most characteristic of the weighty dignity of the Latin language. Greek is subtle, pliant, effervescent; Greek prayers in the Easter rites are long poetic rhapsodies strewn with flowers of rhetoric. Latin is poor, austere, but with a stately dignity that exactly suits the Roman character. So in the Roman Latin rite we have such a trampling march of syllables as: “Sicut illis magnificentiam tribuit sempiternam, ita nobis perpetuum munimen operetur.”

Then comes the final clause “Per Dominum nostrum,” that ends all Western prayers. (pp 249-250).

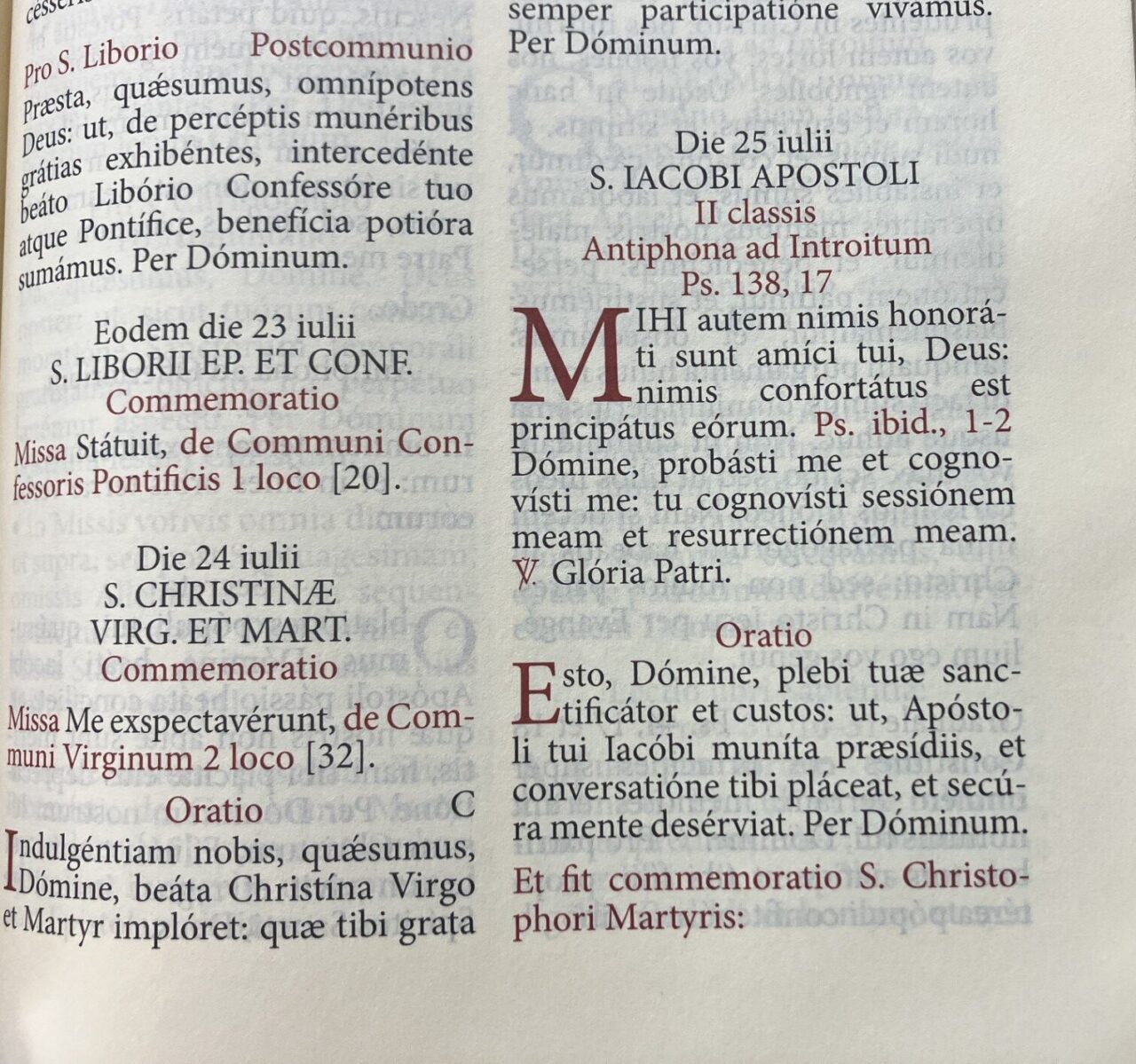

Let’s look at the Feast of St. James, the Apostle:

Oremus. Esto, Dómine, plebi tuæ sanctificátor et custos: ut, Apóstoli tui Iacóbi muníta præsídiis, et conversatióne tibi pláceat, et secúra mente desérviat. Per Dóminum nostrum Iesum Christum, Fílium tuum: qui tecum vivit et regnat in unitáte Spíritus Sancti Deus, per ómnia sǽcula sæculórum.

Here’s the English translation, but we’ll analyze the original Latin.

Let us pray. Protect Your people and make them holy, O Lord, so that, guarded by the help of Your Apostle James, they may please You by their conduct and serve You with peace of mind. Through Jesus Christ, thy Son our Lord, Who liveth and reigneth with thee, in the unity of the Holy Ghost, God, world without end.

- First, the address to God: Domine

- Second, the dependent clause: ut, Apóstoli tui Iacóbi muníta præsídiis, et conversatióne tibi pláceat, et secúra mente desérviat

- Third, a petition: Esto plebi tuæ sanctificátor et custos

- Fourth, the closing: Per Dominum nostrum…

For a helpful podcast episode, which contains more than just details on the Collect, visit here.

Leave a Reply